To foster cleaner growth, China will refuse to accept 24 types of material for recycling, as Zheng Jinran reports from Beijing, with Angus McNeice in London and Aaron Hagstrom in New York.

China’s ban on the importation of several types of solid waste is likely to come into force in March. The move has proved controversial, though, as China is a major market for global recyclables, and some exporting countries, including the United Kingdom and the United States, say it will cause a certain degree of turmoil.

The planned ban has already affected a number of companies in China, forcing them to close or suspend production, but experts claim it is urgently needed to protect the environment and public health, and will lead to an upgrade of the recycling sector.

On July 18, China notified the World Trade Organization that it would impose a ban on the importation of 24 types of solid waste in four classes, including unsorted waste paper, textiles and plastics by the end of the year, according to a WTO document.

The ban was proposed because of the “large amounts of dirty or even hazardous waste” polluting China’s environment, the document stated.

A statement issued by the Bureau of International Recycling, a global alliance of recycling businesses in Brussels, said China later told the WTO that it would adopt new environmental standards for certain types of waste on Dec 31, and proposed March 1 as the day the ban would come into force, although the date has not yet been officially confirmed.

Since the move was announced in July, it has had an impact on both the global and domestic markets.

Shrinking export market

China has been a major processing center for waste for many decades, with imported waste recycled to provide raw materials for the manufacturing sector.

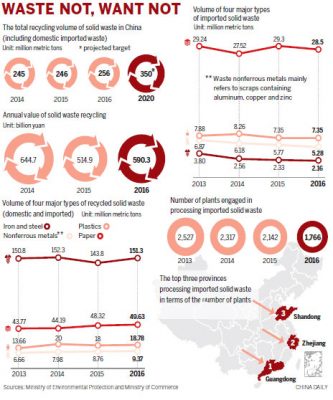

In 2016, more than 43 million metric tons of scrap iron and steel, nonferrous metals, paper and plastics were imported, with nonferrous metals alone valued at $8.42 billion, according to Ministry of Commerce data.

In addition, the largest sources of waste, including the US and European countries, are heavily reliant on China’s recycling industry, so they are already feeling the impact of the ban and struggling to deal with the soaring volume of domestic waste.

Landfill and incineration costs are high in Europe, while other countries are likely to charge more than China to accept waste, according to Meadhbh Bolger, a resource use campaigner at Friends of the Earth Europe.

In 2016, the UK collected 2 million tons of mixed paper for recycling, exporting more than half to China. Around one-third of plastic collected for recycling in Europe was sent to China.

Simon Ellin, chief executive of the UK Recycling Association, said the UK government has been “asleep at the wheel” since China announced the partial ban, which followed the introduction of restrictions on waste imports phased in over the past four years.

“We could have a big problem on our hands,” he said. “Where is the material going to go? I expect that in the first quarter of next year, we will see the UK awash with mixed paper.”

The US is confronted by a similar situation. Restrictions on the export of waste mean it is losing money, while it is spending time and energy attempting to find countries that will deal with the recyclable material China will no longer accept.

Recyclables and waste are the sixth-largest US export to China. In 2016, almost 50 percent of its commodity-grade scrap metal, paper and plastic was sent to China, according to the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries in Washington.

“Our industry is on tenterhooks right now because of the impact on these high-value scrap commodities, which our members send almost exclusively to China,” said Adina Renee Adler, a senior director with the institute.

Some companies, such as Rogue Waste Systems, a waste collector in Oregon, have started to slow processing work to meet the higher quality standards imposed by China, and have sought help from local authorities to allow them to bury excess material in landfills, as indoor stage facilities are full.

In November, the European Union, the US, Japan, Australia and Canada questioned the broad scope of the ban and asked China for a longer transition period of up to five years, according to the statement issued by the WTO.

Domestic effect

The strengthened restrictions on some recyclable waste have also affected Chinese companies that rely on foreign recyclables, especially paper and plastics.

The Ziya Circular Economy Industrial Zone in Tianjin is the largest recycling facility in North China and was home to 387 companies by December. Now, some companies have closed or suspended activities as a result of the fall in the volume of imported waste.

“About 90 percent of the materials for companies that process plastic waste were imported, so they have been affected by the planned ban,” said Tang Guilan, deputy director of the zone’s management committee, adding that 96 plants used to process imported waste, but only a few are still operating.

It’s estimated that next year, the zone’s approved import volume of recyclables will be 118,000 tons, half the number in 2016, she said, noting that the volume of imported waste in the zone fell as stricter regulations were implemented in recent years.

Tang said the affected plants are being encouraged to turn to domestic suppliers to replace imported waste, but conceded that it will take time to shift their materials.

Some plants in Tianjin started processing imported solid waste from the US, Canada, Japan and South Korea in the 1980s, and many relocated to the industrial zone in 2003, establishing a recycling system based on the steady supply of material, Tang said.

According to Xue Tao, deputy head of the E20 Environmental Platform, a domestic environmental protection service, imported solid waste is cheaper to buy than some domestically sourced raw materials as a result of lower costs in the countries of origin.

He added that plants that rely on imported waste in other areas of China will also be affected, especially in the paper and plastics scraps industry, considering the large volume of imported recyclables.

In 2016, China processed more than 49 million tons of waste paper, with 28.5 million tons, or 57 percent, coming from overseas. Of the 18.78 million tons of plastic scraps processed in the same year, 39 percent, or 7.35 million tons, was imported, according to data from the Ministry of Commerce.

“Imported plastic and paper scraps accounted for a large proportion, thus the ban will significantly raise costs at processing plants, which will definitely have an influence on plants that rely on processed paper and plastic materials in the short term,” Xue said.

In addition, stricter regulations have seen import volumes fall in recent years, which has resulted in a reduction in the number of companies processing imported waste nationwide, from 2,527 in 2013 to 1,766 in 2016, data from the Ministry of Environmental Protection showed.

“By adopting the ban, China plans to change the current global structure in the division of work, eradicating its role as a dumping ground for leftovers from developed countries, which has grown in the past 30 years,” Xue said.

The ban caters to a growing demand for sustainable development and public calls for a cleaner environment in recent years, and it’s a step China urgently needed to take, he said.

Therese Coffey, parliamentary undersecretary at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in the UK, said the ban may not be all bad news for Britain.

“It gives us an opportunity to reprocess more here, rather than exporting to the other side of the world just because it’s a bit cheaper to do so,” Coffey told the UK Environmental Audit Committee in November.

Seeking replacements

In the US, some processors are trying to find markets to replace China.

Xu Haiyun, chief engineer of the China Urban Construction Design and Research Institute, said the planned ban demonstrates the central government’s strong determination to curb pollution from imported solid waste, which is quite encouraging, but he added “implementation may be not easy”.

China has not established a household garbage sorting system or a waste-recycling network, which means a massive amount of waste ends up in landfills and incinerators, he added.

Xue, from E20, is optimistic about progress in establishing a recycling network before 2020 as a result of government support and rising private sector investment.

Domestic recyclers may discover replacement sources of solid waste soon, he said.

Pilot garbage-sorting projects have been established in more than 20 cities, and there are plans to boost the recycling industry so the total volume of recyclable waste grows from 256 million tons in 2016 to 350 million tons by 2020, according to statements from the central government.

More measures have been adopted to regulate solid waste imports, because the materials are often dirty, poorly sorted or contaminated with hazardous substances. Even when such waste is safely imported, it is not always recycled properly.

For example, in Tianjin, highly-polluting processing plants have been corralled in the Ziya Circular Economy Industrial Zone, and special equipment is used to tackle the pollutants emitted, according to Tang Guilan, the zone’s deputy director.

Moreover, the zone strictly supervises every container to ensure that imported recyclables are processed inside the facility and no contaminated products are allowed to leave.

The 387 companies in the zone can process more than 1.5 million tons of solid waste, including imported material, every year, providing ample material for the domestic market, such as 300,000 tons of plastic products, without polluting the atmosphere.

Regulating solid waste imports is a major issue to protect the environment and public health, so China will employ a range of safety measures and will hit violators hard, said Li Ganjie, the minister of environmental protection.

Wang Keju in Tianjin contributed to this story