|

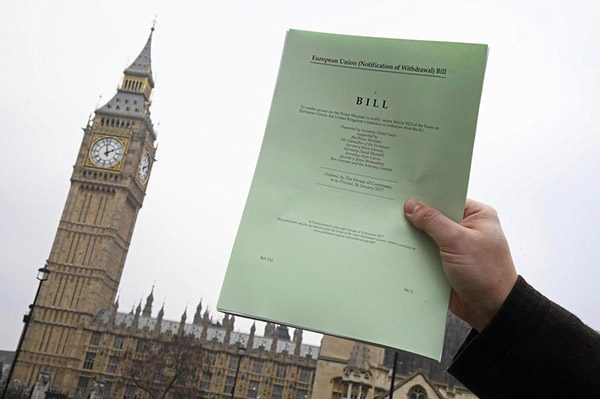

A journalist poses with a copy of the Brexit Article 50 bill, introduced by the government to seek parliamentary approval to start the process of leaving the European Union, in front of the Houses of Parliament in London, Britain, January 26, 2017. [Photo/Agencies] |

LONDON – Britain moved closer to leaving the European Union Wednesday as lawmakers backed a bill authorizing divorce proceedings and kept alive the government’s plan to trigger Brexit talks within weeks.

The House of Commons decisively backed the bill by 498 votes to 114, sending it on for committee scrutiny. The result was a victory for the Conservative government, which had fought in court to avert the vote out of fear Parliament would impede its Brexit plans.

Lawmakers also defeated a “wrecking amendment” proposed by the Scottish National Party that sought to delay Britain’s exit talks with the EU because the British government has not disclosed detailed plans for its negotiations.

During two days of debate in the House of Commons, many legislators — Euroskeptic and Europhile alike — said they would back the bill out of respect for voters’ June 23 decision to leave the EU.

But opposition parties will try to insert more amendments during the next stages of the parliamentary process. They are seeking to prevent an economy-shocking “hard Brexit,” in which Britain loses full access to the EU’s single market and faces restrictions or tariffs on trade.

After committee consideration, the bill is due to return to the House of Commons for a final vote next week before moving on to Parliament’s upper chamber, the House of Lords.

The government was forced to introduce the legislation after a Supreme Court ruling last week torpedoed Prime Minister Theresa May’s effort to start the process of leaving the 28-nation bloc without a parliamentary vote.

The government wants to have the bill approved by early March so it can meet a self-imposed March 31 deadline for triggering the EU divorce talks.

Scores of lawmakers spoke during more than 16 hours of debate over two days. Those who backed the winning “leave” side in the referendum said they would vote proudly to start the exit process.

Others, who voted to remain in the EU, said they would respect the will of the people despite their own reservations.

Former Treasury chief George Osborne, a pro-EU Conservative, said “to vote against the majority verdict of the largest democratic exercise in British history” would set Parliament against the people and “provoke a deep constitutional crisis in our country.”Still others said they would oppose the start of divorce negotiations, accusing the government of rushing Britain toward the EU exit door with little idea of what is on the other side.

The government says it will publish a White Paper outlining its strategy for withdrawal on Thursday, but it’s unclear how many new details it will contain.

“Voting for departure is not the same as voting for a destination,” said Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron, who called on the government to guarantee a second referendum to approve a final deal with the bloc.

Scottish National Party lawmaker Angus MacNeil said that in acting to trigger Brexit, “the House of Commons has taken leave of its senses.””It’s crossing its fingers and hoping for the best,” he said.

The UK’s largest opposition party, Labour, told its lawmakers to back the bill but says it will try to amend it later to prevent an economy-shocking “hard Brexit,” in which Britain loses full access to the EU’s single market and faces restrictions or tariffs on trade— but at a later stage.

However, 47 of the 229 Labour lawmakers defied party leader Jeremy Corbyn and voted against the bill.

“I do not believe that the Brexit course we are now set on will make Britain a more prosperous, fairer, more equal, tolerant country,” said Owen Smith, one of the Labour rebels. “I believe, by contrast, that it will make our politics meaner, and it will make our country poorer.”Meanwhile, Britain’s former top diplomat to the EU warned Wednesday that disentangling the UK from the bloc will be a long and arduous process.

Ivan Rogers, who resigned in January after telling the government that a deal could take a decade, told Parliament’s European Scrutiny Committee that Brexit will involve negotiations “on a humongous scale.” Rogers said consensus among the other EU nations was that a new free trade deal between Britain and the bloc would take until the early 2020s to be ratified.

One major wrangle is likely to be over how much Britain will have to pay the EU to leave. Rogers said EU officials currently put the figure at 40 billion to 60 billion euros ($37 billion to $56 billion).