Residents of the village in which China’s president spent nearly seven years recall a young man determined to improve their lives, as Huo Yan and Li Yang report from Yan’an, Shaanxi.

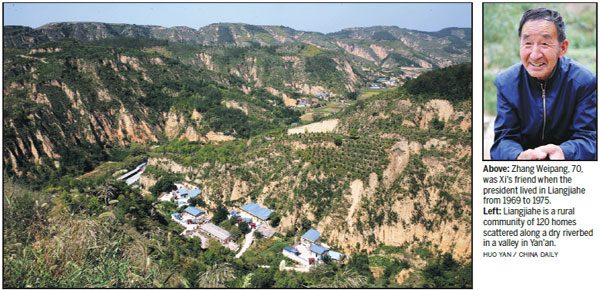

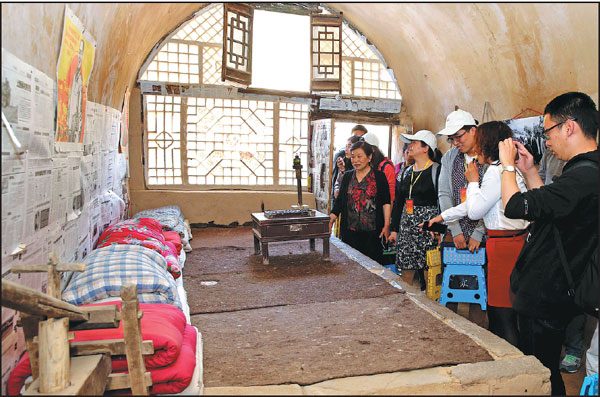

Liangjiahe village, a community of 120 homes scattered along a dry riverbed on the Loess Plateau in Yan’an, Northwest China’s Shaanxi province, looks no different from the other valley hamlets in the region, except for the visitors lined up waiting to board electric minibuses to visit its cave dwellings and crofts.

From 1969 to 1975, President Xi Jinping lived and worked in the village as an educated youth during the “cultural revolution” (1966-76) when he was ages 16 to 23.

It was in this village that Xi, who heads the Communist Party of China, joined the world’s largest political party, which has more than 89 million members.

In 1974, he was elected Party chief of the village committee – the start of his public career – and he was still a resident when he was recommended as a suitable candidate to become a student at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Last year, Liangjiahe received 900,000 visitors, and the number is expected to hit 1.3 million this year. That’s about 3,600 people a day on average. Unlike conventional tourists, some of the visitors are sent in groups by their employers, while others are clad in Red Army uniforms and armed with notebooks and pens, jotting down the things that interest them.

The village is small, and the usual tourist itinerary follows a settled order along a meandering mountain path: the village museum, a farm, a blacksmith’s shop, a biogas digester, a well, a grinder powered by a diesel generator, a grocery store and the cave dwellings.

Apart from the museum and the cave dwellings, the other items are regarded as the heritage left by Xi in the 1970s, and most still function well today.

Xi, who learned about biogas technology in Mianyang in Southwest China’s Sichuan province during a government-led campaign, built the biogas digester with other educated youths and the villagers. He also led local farmers in laying five strips of farmland in the riverbed, as the river, which was once wide, narrowed to a channel, albeit still sufficient to irrigate the land.

Dangerous work

The small stream was the only source of water in Liangjiahe. But the water was sandy. To solve the problem, Xi led the villagers in digging a well. Many seniors remember how he was the first person to jump into the hole, and how he worked the longest shifts in the numbing mixture of ice, water and mud. It was a dangerous job because the well could collapse at any time during the excavation process.

Before the grocery store opened, it took hours for Liangjiahe’s farmers to travel to the shop in Wen’anyi, a nearby town, to buy necessities. Xi suggested that the village committee should buy daily goods from the shop in Wen’anyi and sell them to the villagers in Liangjiahe at the price at which they had been purchased, saving them a lot of time.

Xi also exchanged a motorcycle he had been given by the county government as a reward for his performance for the diesel generator and grinder to help the villagers.

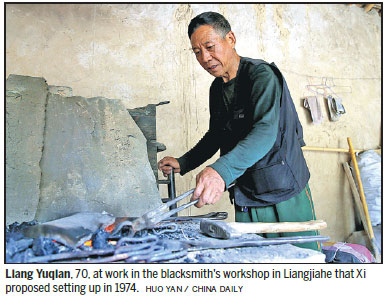

Liang Yuqian, 62, a blacksmith who made farm implements during Xi’s time, still runs the same workshop, which opened in 1974 after Xi invited him to move from his home village nearby to work in Liangjiahe.

“At first I just wanted to move from village to village. But Xi persuaded me to stay. He talked about his plan cordially with me, saying my plan would bring more personal profit, but that working in one place would mean I served more people,” he recalled.

When Xi revisited Liangjiahe in February 2015, he recognized Liang immediately and greeted him with the words “Are you still doing the job?”

Liang Yuming, 75, who Xi replaced as village committee Party chief in 1974, said the heritage items represent just a small part of Xi’s contribution to Liangjiahe because he also did many other things, such as teaching the villagers to read and write, along with history and geography. He also soothed relations between families.

Liang Yuming said Xi was the youngest of the six educated youths from Beijing who were assigned to Liangjiahe – Xi was age 16 when Liang Yuming met him for the first time in January 1969 – and he was the one who most loved reading books.

He recalled Xi’s two suitcases were the heaviest because they were filled with books.

“When the farmers, who were used to hard outdoor labor, helped to carry the young men’s luggage they said Xi’s suitcases were too heavy and it was a wonder that a 16-year-old could carry them all the way from Beijing on the three-day journey to the remote valley,” he said.

Lei Pingsheng, who was Xi’s roommate and is now a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, said Xi’s passion for knowledge was impressive. “When we woke up late at night, we often found him still reading carefully in the dim light of an oil lamp surrounded by darkness and quiet.”

Xi likes reading about history, politics, economics, philosophy and literature, and comparing notes with people who share the same interests, according to Lei.

“The educated youths shared their books. For most of us, learning seemed to be a part of life, undisturbed by the political movement swirling in our faraway hometown of Beijing,” he added.

What made Xi different from the other bookworm educated youths was that he was always ready to put what he had learned into practice to serve the people.

“Since his youth, it has been Xi’s unswerving belief to undertake practical work for the people,” said Tao Haisu, an educated youth from Beijing who was in the same county as Xi and often communicated with him about history and literature.

One time, Xi encouraged a difficult villager, who was often fiercely criticized for being a thief, to sing his favorite folk song to the villagers who were preparing to criticize him at a meeting. The man sang well and with great emotion, moving many of his potential critics. From then on, he was a changed man and was accepted by his neighbors.

“Although Xi is five years younger than me, he reads more books and is knowledgeable in more fields than me,” Tao said. “He is honest and trustworthy.”

Many people believe that the hard life he led in Liangjiahe played an important role in preparing Xi’s resolve to serve the people.

Uncertain future

Wang Yansheng, another educated youth from Beijing who was also Xi’s roommate at Liangjiahe, said: “Xi is honest in admitting he was unsure about the future when he first arrived at Liangjiahe. Everybody has a process of development. No man is great when he is born.”

Wang vividly recalls the “four difficulties”, as Xi noted, that affected every newcomer to Liangjiahe: fleas, shortage of food, hard work and uncertain thoughts.

Lei said they were shocked by the poverty of the region when they first arrived in Yan’an, which was known as “a holy land of revolution”, as the Party’s main organs had stayed and developed there for eight years.

“Some people slapped the roof of the truck’s cab and asked the driver if he was lost,” Lei said.

After Spring Festival in January or February, the village was almost empty, because most of the farmers left to live as beggars and try to alleviate the lack of food during spring, according to Zhang Weipang, 70, a villager and good friend of Xi’s at the time.

“The hand-to-mouth life of the farmers prompted Xi’s sympathy and motivated him to strive for a better life for the people,” Zhang said.

The tourist boom in the village thanks to Xi’s “heritage” has brought great convenience to the local people.

Xi never complained about the harsh conditions at Liangjiahe. He chose to put up with them and made up his mind to change them, according to the villagers.

“Xi’s tolerance of hardship was beyond my expectation. He just took things as they came. When he worked on the farm, he was like a professional farmer,” said Liu Jinlian, a 67-year-old villager.

For the first two months after their arrival, Xi and the five other educated youths lived in a cave dwelling in Liu’s home. Xi visited the family during his 2015 visit, and inquired in detail about every family member and their living conditions.

Lei said an important reason for Xi’s love of, and gratitude to, the people at an early age was his family education. Xi told him that the farmers were the fathers and mothers of the Red Army, and were it not for their selfless sacrifice China’s revolution would not have succeeded.

According to Lei, Xi became more experienced, patient and confident after he visited his father Xi Zhongxun, a former vice-premier who was wrongly investigated, between 1970 and 1972.

After that, Xi decided to live and work as a “common farmer”, regarding himself as a part of the “yellow earth”, Lei said.

Xi met a beggar who said he used to be one of Xi’s father’s guards. After the beggar related the names of Xi’s family members and a few other details, Xi not only gave him all the money he had that day, but also gave his coat to the old man, Lei said.

During his 2015 visit to the village, Xi’s biggest concern was still the people’s livelihoods, according to local resident Zhang Weipang.

“He asked me whether I often ate meat and what I planted. As before, his questions were always down-to-earth and concerned the specifics of people’s lives,” he said.

‘Spiritual home’

The villagers in Liangjiahe have written to Xi four times since 2007 to tell him about the latest developments. Xi replied to their letters every time, expressing his nostalgia – he calls Liangjiahe his “spiritual home” – and sending his best wishes for the village’s development.

According to Gong Baoxiong, village committee chief, the village set up a tourism company in 2015, creating enough jobs for the farmers to work at home. Since 2007, the village has had a new road, internet, running water, electricity and most modern facilities. The main sources of income are tourism, root crops, apples, vinegar and pickled vegetables.

Gong, in his late 30s, said: “President Xi said he ‘secured the first button of his life well’ at Liangjiahe. That provides motivation for all young civil servants to integrate serving the people with their careers and also their lives.”

“He asked me which family I came from,” said Gong, as he recalled his chat with Xi during the visit two years ago. “When I said my father’s name, President Xi smiled and said ‘I know him. He is an honest man.'”