On a sunny March afternoon, Fan Shenghua sits in front of a big metal basin in his workshop, heating up fresh West Lake Longjing tea leaves.

Every morning, workers climb up a mountain to pick tea leaves behind Longwu village, one of the most famous places for growing West Lake Longjing tea.

In the afternoon, he heats up the collected leaves, a procedure that halts oxidation shortly after harvest and seals in the botanical magic.

West Lake Longjing tea is one of China’s top teas and is grown only in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province.

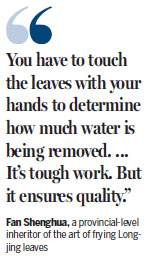

Properly heating the leaves, known as panning, is essential to the quality of the tea, and it was listed as a national-level intangible cultural heritage in 2008.

The Fan family has grown and produced Longjing tea for generations.

“I started to learn the tea-panning skill when I was 14. And I haven’t skipped a year yet,” the 56-year-old master said proudly.

Panning tea is physically hard work. Fan shows a photo of his hands, with blisters and peeling on the palms and fingers. He has to do it with bare hands in a metal basin with temperatures up to 260 C.

“You have to touch the leaves with your hands to determine how much water is being removed,” Fan said. “The length of time depends on when the leaves are picked, the weather and the drying time.”

It takes him four to five hours to complete all the processes for each batch of finished tea, and he can process up to 10 kilograms in one day.

Most villagers have now purchased machines to do the work, as they are more efficient and faster.

“The young generations could not endure such hardship,” he said. “It’s tough work. But it ensures quality.”

“It’s easy to see if it is machine-processed, because it floats longer in the water and tastes more astringent.”

Fan worries that one day no one will be able to make Longjing tea by hand.

He taught classes in school and had dozens of apprentices, “but no one lasted for more than one year. They come and go.”

Fan’s newest apprentice is Zhou Yunfeng. He practiced during summer and autumn last year, and this was his first day of the spring tea season.

The 19-year-old from a nearby village is a student from West Lake Vocational High School.

“I learned about the tea culture when Master Fan came to give classes in my school. I found I was quite interested in it, so I enrolled as an apprentice. I think I can bear all the hardships,” Zhou said.

According to his master, Zhou was talented. “He has bigger palms that can hold more leaves and more sensitive hands. I’m confident of teaching him all my skills,” said Fan.

The average price of Fan’s handmade tea is double or triple what is charged for machine made tea, reaching 6,000 yuan ($898) per kilogram. “He can make a good living if he can stick to it.”

Fan’s son, who majored in tourism, will graduate from university this year. He taught him the skill and hopes it will become his career.

“He must produce tea. It’s tradition. We need to pass it along. Still, young people have their own ideas,” said the father.