There is almost no space to stand in Xiong Wenyi’s storeroom in Jiangxi province. It is filled with every kind of lock you could imagine, made from wood, brass and iron.

Xiong has been obsessed with collecting locks for more than 30 years. “I have over 10,000 items in more than 100 different styles, with the oldest one dating back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD),” he said.

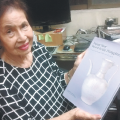

The collector, in his 50s, showed one of his prized possessions: a pull lock, which has a small hook with which to pull the key. Xiong held up another device that requires an extra step to unlock. “You have to turn the key and press the button on the bottom to unlock it,” he said.

His collection also includes a large wooden lock once used on a city gate in Shandong province that can be traced back to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). “This wooden lock is difficult to preserve,” Xiong said.

One of the locks he is most proud of finding is a so-called maze lock from Nyingchi prefecture, the Tibet autonomous region. “It’s called maze lock because the inner structure is a zigzag,” he said. “It’s easy to unlock but very difficult to copy the key, as it needs to fit the exact angle and length at each turn.”

The lock was made during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Xiong paid a Nyingchi resident a daily stipend of hundreds of yuan to search for the rare lock in rural areas of the prefecture during the winter of 2015.

The vast lock collection began to take shape in Xiong’s childhood, when he saved money to buy stamps, candy wrappers and small locks from his peers. “I see folk wisdom in ancient locks. It’s easy to see how smart our ancestors were when looking at their locks,” he said.

The design and craftsmanship of the locks has amazed visitors at various exhibitions Xiong has attended.

But the value of the collection far exceeds the locks themselves, according to Hong Jun, a historian from Wuhan University. He said the collection allows the public to observe the development of Chinese lockmaking over thousands of years.

“They are important in the study of China’s national storage and guard systems, public security and aesthetic standards,” Hong said.

Yet Xiong said the larger his collection of locks became, the more pressure he felt.

“Ancient locks, especially wooden ones, are easily damaged or broken. I must work quickly to preserve these artifacts for future generations,” he said.

In 2012, he decided to set up a lock museum, but his plan was put on hold when he was diagnosed with cancer. Facing death, Xiong said his lock collection gave him the strength to fight the disease: “I told myself to hold on because more people need to see my locks.”

After making a recovery, Xiong increased his efforts to collect more locks. He hired more than 20 seniors nationwide to help search for specific devices. He bought them smartphones so that they could send him pictures of new discoveries.

“I want to fulfill my dream of setting up a lock museum to unlock the folk wisdom of our ancestors,” Xiong said.